The Bangor refugee resettlement office run by Catholic Charities Maine is planning to move 150 migrants into cities and towns within a 100-mile radius of Bangor over the next year.

Catholic Charities Maine is one of three nonprofit organizations in the state that has been designated by the federal government to be a refugee resettlement agency, alongside the Lewiston-based Maine Immigrant and Refugee Services (MEIRS) and the Jewish Community Alliance of Southern Maine, based in Portland.

Under the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP), the president sets a ceiling for the number of migrants the U.S. will accept annually as refugees, who are defined under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) as foreign nationals who are facing humanitarian concerns or persecution in their home country.

Refugees are a separate population from asylum-seeking migrants, who may cross the border into the U.S. illegally before being apprehended and making an asylum claim, and then live in the country for several years awaiting the adjudication of their asylum application.

Refugees are vetted by the federal government prior to their admission, and, unlike asylum seekers, refugees are allowed to work immediately upon arrival in the U.S., and can usually apply for citizenship within five years of their arrival.

In fiscal year 2024 (FY24), President Joe Biden set a target for a total of 125,000 refugees to be resettled in the U.S., a number which the Biden administration reportedly plans to maintain for FY25.

“The refugee program is different from this influx of asylum seekers, even though people sometimes erroneously equate refugees and asylum seekers,” said Jessica Vaughan, Director of Policy Studies at the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS).

“The refugees are identified through a process and in partnership with the United Nations refugee program,” Vaughan said. “And so these are people who are displaced from their home country and are deemed to be in need of resettlement – as opposed to asylum seekers, who, under current policies, is pretty much just anyone who comes across the border illegally and claims to have a fear of returning to their home country.”

Vaughan said that while there is a more thorough process for vetting refugees than for the migrants who are apprehended at the southern border, the background check process is not foolproof, as refugees are often coming from countries with dysfunctional governments that do not keep adequate records.

The federal government works with state partners, often either municipal or county offices, or non-governmental organizations such as Catholic Charities, to disperse the admitted refugees and resettle them in communities across the U.S.

Those state partners are given federal grants to provide various taxpayer-funded services to the refugees, including housing, English language classes, medical treatment, employment services, and cash assistance.

“Theoretically, there is supposed to be some kind of coordination with receiving communities, but that is not exactly what happens. They do not always notify receiving communities that they’re planning on bringing refugees in to be resettled,” Vaughan told the Maine Wire.

A total of 419 refugees were resettled in Maine during FY23— a number which the state’s resettlement agencies said increased to 840 in FY24.

At a meeting of the Bangor City Council’s Government Operations Committee last week, representatives from Catholic Charities Maine’s Bangor office told city officials that over the next fiscal year they are expecting to resettle 150 refugees in the greater Bangor area, up from 100 refugees in FY23.

Presenting to the committee on the nonprofit’s resettlement plan was Stephen Letourneau, CEO of Catholic Charities Maine, and Melissa Bucholz, the assistant director of their Bangor Refugee and Immigration Services (RIS) program .

Bucholz began the presentation with a detailed demographic overview of the populations who receive services through the organization’s resettlement office.

The Bangor resettlement office serves both refugees and migrants admitted under Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs), as well as asylees, trafficking victims, secondary migrants, Cuban and Haitian parolees, and humanitarian parolees from Ukraine.

Bucholz said that as of June 10, Catholic Charities Maine had resettled 84 out of the expected 100 refugees for FY24 in the greater Bangor area, as well as two Ukrainian parolees, 11 Cuban or Haitian entrants, and one asylee.

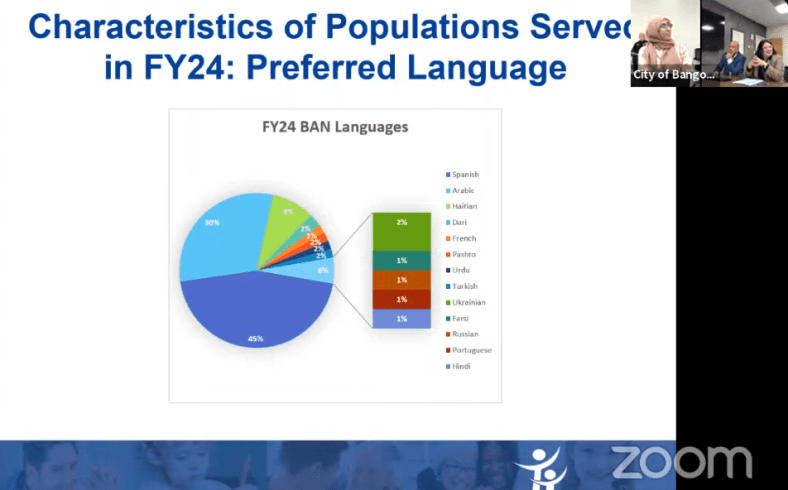

Of those refugees resettled by the nonprofit in the Bangor area in FY24, the majority were of either Syrian (36%) or Venezuelan (29%) origin, and 75 percent reported Spanish or Arabic as their preferred language.

About 26 of the refugees resettled in and around Bangor in FY24 arrived as individual migrants, while 21 were admitted as a family unit, with an average size of nearly four members, according to Bucholz.

According to data from the U.S. State Department, a total of 530 refugees from 18 different countries were resettled in Maine statewide in FY24.

That figure includes 135 refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 155 from Syria, 52 from Venezuela, 48 from Iraq and 38 from Somalia.

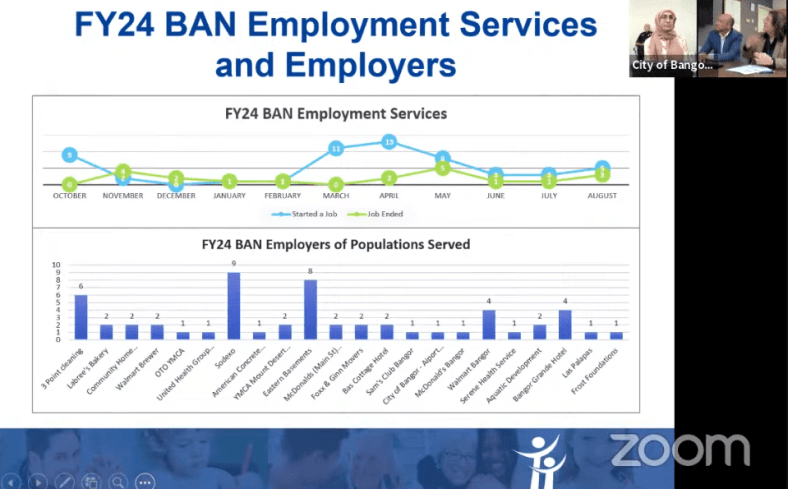

Out of a total of 64 employable adult refugees (aged 18-64) resettled in the Bangor area this year, Catholic Charities Maine reported that 56 had found jobs across 22 different employers.

“A refugee, the day they arrive — which they’re arriving at the invitation of the federal government, which is why we don’t have control over when they do it — they can work day one, if they’re an employable adult,” said Catholic Charities Maine CEO Stephen Letourneau.

“It’s up to the agencies that are resettling them like Catholic Charities to prepare them, set them up for success and make the arrangements with particular employers,” Letourneau said.

Bucholz then went on to describe the Bangor resettlement office’s plans for FY25, which begins on Oct. 1, 2024, and ends in September 2025.

“With our resettlement office, we work within the 100-mile radius [of Bangor], usually that’s focused on Bangor and surrounding communities, but we can work within that 100 mile radius, and we are hoping to resettle 150 individual refugees in [FY25],” Bucholz said.

Bucholz described the resettlement plan as a “moderate increase” over the 100 refugees resettled by the Bangor office in FY24.

After the presentation concluded, Bangor City Councilor Carolyn Fish asked Bucholz to elaborate on where Catholic Charities Maine plans to resettle the refugees within the 100-mile radius around the city.

Bucholz said that the data presented regarding the office’s FY24 resettlement was specific to Bangor, but that Catholic Charities Maine frequently looks outside of the city to Old Town, Orono and Brewer to find affordable housing for the refugees.

“You have the capacity to resettle within a 100-mile radius, it’s just the closer to proximity of our staff, the more successful they generally are,” Letourneau told Fish. “The Multicultural Center has been really fantastic for the success of this program, and so generally it’s around the Bangor area.”

The Bangor-based Maine Multicultural Center is a nonprofit organization founded in 2016 that coordinates with several area partners to provide “integrative services” to migrants, such as English language classes, health care, and workforce development programs.

Bangor City Councilor Dina Yacoubagha, who immigrated to the U.S. from Syria over 25 years ago, works as the program manager as the Maine Multicultural Center and sits on the State of Maine Permanent Commission on the Status of Racial, Indigenous and Tribal Populations (PCRITP).

The Maine Wire reached out to officials in Old Town, Brewer and Orono to ask if Catholic Charities Maine had told them about their plan to resettle refugees in their towns, and if they had concerns related to the area’s housing shortage and stress the resettlement could place on their social services programs.

Old Town City Manager Bill Mayo said on Friday that the city “has no services or facilities to deal with 150 refugees.”

“I can’t comment for Bangor, but even a community of that size is likely going to struggle with trying to absorb that many people without some type of state/federal assistance,” Mayo wrote in an email to the Maine Wire.

Mayo added that while he knew about the refugee program, Catholic Charities Maine had not contacted him to coordinate the resettlement in Old Town.

Maine’s housing shortage is likely to complicate any plans to re-settlement refugees in the state.

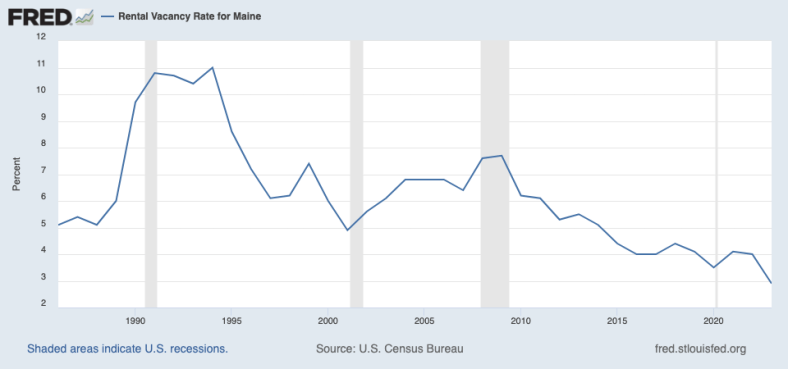

According to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve, Maine’s rental vacancy rate is lower than at anytime since 1986.

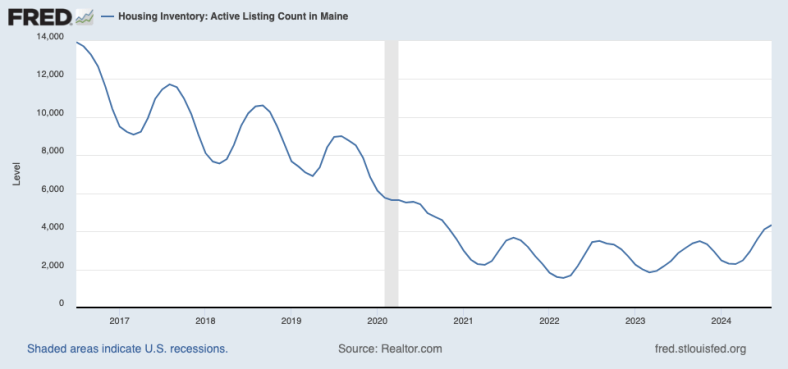

The number of homes actively listed for sale also remains near generational lows.

Jessica Vaughan of CIS said that the plan to resettle the refugees within a 100-mile radius is likely an acknowledgement that the housing supply in Bangor alone cannot accommodate the number of refugees.

“They clearly understand the challenges of this and recognize that they’re going to have to be spreading all these people out,” Vaughan said, adding that this can sometimes be advantageous as “the communities receiving them can actually handle it, will give them meaningful assistance, and that they’re more likely to assimilate into the community and be able to find work and support themselves.”

Although refugee resettlement is often couched as a moral prerogative, there’s also a profit motive for both the resettlement agencies and the potential employers.

Describing the relationship between NGOs, employers and the federal government, Vaughan said that refugees “are low wage workers that [employers] know are going to be subsidized by taxpayers.”

“The contractors, like the NGOs, make money off of it because they’re paid to do this resettlement,” said Vaughan. “The employers know that they will be able to keep their labor costs very low, so that’s good for them and their bottom line. And taxpayers are left covering the gap between what the refugees are going to earn from these low wage jobs and what they’re going to need to survive.”

City Councilor Susan Deane expressed concern that the housing shortage in the Bangor area could be exacerbated by the refugee resettlement, and asked the Catholic Charities Maine representatives if they have a relationship with area hotels or motels where they place the migrants.

“Usually we work with landlords prior to [the refugees’] arrival,” Bucholz responded. “There’s some landlords we’ve been working with in the area to get folks placed in permanent housing as soon as possible when they arrive.”

Letourneau said that Catholic Charities Maine “tried really hard not to utilize hotels at all” in their resettlement efforts.

Councilor Fish then asked if the landlords have any financial incentive to work with Catholic Charities Maine and rent to refugees.

“There are no exceptional financial benefits,” Letourneau said. “They will get a market rent usually, but it’s nothing above and beyond.”

The Catholic Charities Maine CEO claimed that “the more people learn about [immigrants] the more people want to help them.”

“I think there are many people that own units and have capacity within their system, or they might be immigrants themselves, and so they want to help,” he added. “We’ve had people reaching out to us to say ‘hey, do need apartments or homes to rent?'”

Fish reiterated concerns about the housing crisis in the Bangor area, saying “we have Bangor residents, we represent Bangor residents, and 100 or 150 a year, 150 apartments is a pretty significant impact within our community.”

“While we’re very compassionate, and you know, want to help people that are definitely struggling and in worse situations than we are here in America and Bangor, at the same time, a hundred apartments, or a hundred fifty, is pretty significant,” Fish said.

Letourneau, while admitting that there is a housing shortage, said that due to many of the refugees arriving as families, the number of apartments they would be taking off the market would be closer to 25 or 30 units.

“There are challenges, significant challenges, especially around housing — actually, it’s a lot worse than Portland,” Letourneau said. “But I think we’re overcoming that, because it’s been a good community approach.”

Letourneau then drew a comparison between the “planned approach” of refugee resettlement versus the waves of asylum-seeking migrants that have arrived in Maine in recent years.

“Something like refugee resettlement, which is a much more planned approach to immigration, versus, you could get 500 people within a week from the southern border that are asylum seekers,” he said. “I mean, that’s happened, big migration into Portland at different times — there’s absolutely no control over that.”

“At least with refugee resettlement, it’s a planned approach that’s proactive,” he added.

Catholic Charities Maine is a major recipient of government grants, and in recent years received millions of taxpayer dollars from federal agencies to provide cash and medical assistance to refugees.

In 2024 so far, Catholic Charities Maine has been awarded $4.9 million under the federal Refugee Cash and Medical Assistance (CMA) Program, under which refugees receive taxpayer-funded cash and medical assistance for up to 12 months after their arrival in the U.S.

From 2020 through 2023, Catholic Charities Maine has a received a total of about $21 million in federal grants related to various refugee assistance programs.

0 Comments